'Analyzing the presence of female authors in secondary and university tuition curriculums we find that much remains to be done'

Teresa López Pellisa, PhD Assistant at the Department of Spanish Philology, Communication and Documentation of Universidad de Alcalá, comments to uah.esnoticia the main trends in the research of Spanish and Latin American fantastic literature. In this interview, Teresa explains the concepts she works on in her research work.

- Why have monsters taken strength in a context like the current one?

Monsters have always existed. Their presence in the symbolic imagination of humanity has accompanied us since the beginning of time. If we think about chimeras, demons and wolfman, ghost, Dracula (which emerged in the 19th century) or the zombie in the Haitian tradition, we can see that at every moment in history human beings have generated different monsters that reflected fears, desires, phobias and repression of the society in which they were generated.

Today, the monsters have been mutating and adapting to the interests and needs of society. Today we can talk about hegemonic monsters when we attend the creation of zombies produced by the virus of a laboratory that responds to economic interests (as happens with the stage play 'Banqueros vs zombies' ,'Banckers versus zombies', by Dolores Garayalde and Pilar G. Almansa) or about political monsters when we speak of ghosts that return to denounce that they were murdered by the dictatorship or that they were victims of a social state of law that did not protect them as it should (I am thinking in this case of some tales by the Argentine writer Mariana Enríquez).

- Where does the need to study fantastic figures in literature come from?

Fantastic literature is subversive because it reveals that reality is a convention that can be transgressed at any time, and science fiction literature has very strong political potential because it allows us to think that another world is possible. One of the characters I've been most interested in addressing in my work is that of the artificial woman from what I call Pandora's Syndrome. When I started working on the representation of artificial female characters in science fiction I began to collect and study artificial women, life-size dolls, gynoids (female androids), mannequins, virtual women, etc. With Pandora's syndrome I mean the texts in which a male manufactures/buys a life-size artificial woman to have a sentimental relationship with the artifact, so he becomes a technopater and lover of the creature. Most of these texts close with a tragic (pandoric) ending that penalizes the relationship between the human and the non-human.

The submission of the female subject or the continued role of the artificial woman is not penalized as heteropatriarchal utopia. What is penalized is the impossibility of heterosexual reproduction of labor and the impossibility of the production of bodies for the capitalist institutional system.

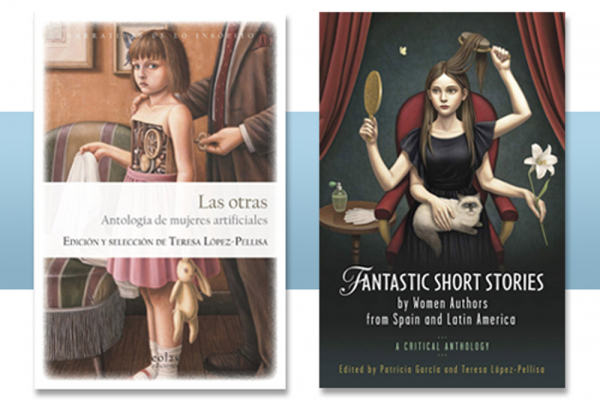

As a result of this research, the publication of 'Las otras. Antología de mujeres artificiales' (The Others. Anthology of artificial women) in which stories are gathered on this subject in which a clear feminist posture is shown, such as those of Angelica Gorodischer and Elia Barceló, as well as other stories reflecting on the theme of the LGBTI collective, with proposals that subvert the function of the female body as heteropatriarchal fetish, as is the case of the stories by Lola Robles, Naief Yehya and Alberto Chimal, in addition to proposals for sexual relations with absolutely 'queer' beings that play at having a feminine appearance, as proposed by Joss and Diego Muñoz Valenzuela. But there are also monstrous maternities (as in the stories of Claudia Salazar and Gerard Guix) or other texts in which the eroticization of the female body is not the central axis of the story, as in the stories of Lina Meruane, Edmundo Paz Soldán, Mar Gómez Glez, Sofía Rhei, Jorge Baradit, Alicia Fenieux, Ricard Ruiz Garzón, Iván Molina or Sergio Gaut vel Hartman, as well as other tales in which the relationship between the male and the artifact would be inserted into the tradition initiated by Hoffmann's 'El hombre de arena' ('The Man of Sand', 1816), such as the tales of José María Merino, Patricia Esteban Erlés, Pablo Martín Sánchez, Juan Jacinto Muñoz Rengel, Raúl Aguiar, Ana María Shua, David Roas and Guillermo Samperio.

|

| Teresa López Pellisa |

- In relation to the work ‘Ciberfeminismo: De Venus Matrix a Laboria Cubonik’ ('Cyberfeminism: From Venus Matrix to Laboria Cubonik'), are more fantastic female characters found today than in the past? What do you think is the origin of this phenomenon?

The book on 'Ciberfeminismos: de Venus Matrix a Laboria Cubonik' consists of an anthology of theoretical, essayistic, academic and artistic texts of different thinkers on the relationship between feminism and digital culture, so it would not be related to fantastic literature.

This publication has an extraordinary prologue by Remedios Zafra, , whose work in this field of research is remarkable at the international level. This thinker was the introducer of cyberfeminist theories in the Spanish academic field in the 90s. Some of the texts that are reflected here are translated for the first time into Spanish, so anthology is articulated from a historical perspective that it addresses from the VNS Matrix manifestos of the 90s, to the xenofeminism of Laboria Cuboniks in the 21st century, or the bio-tech activism of SubRosa, as well as Rosi Braidotti's posthumanism or Judy Wajcman's technofeminism.

- Finally, can you tell us what research you are currently working on within the UAH?

One of my main research lines is focused on rescuing and making visible the work of Spanish and Latin American writers in fantasy and science fiction. As a result of these investigations, several publications have emerged such as 'Poshumanas y Distópicas. Antología de escritoras españolas de ciencia ficción' (Posthuman and Dystopian. Anthology of Spanish science fiction writers) whose work I edited with the writer Lola Robles. The interesting thing about this anthology is that it shows a historical perspective that spans from the 19th century to 2015, in which names appear like that of Emilia Pardo Bazán, author that we associate with naturalism and realism, although she wrote numerous fantastic and wonderful stories, as well as some sci-fi story. In fact, his first novel, 'Pascual López. Autobiografía de un estudiante de medicina' (Pascual López. Autobiography of a medical student, 1879)' had a rational resolution for the extraordinary phenomenon, and therefore, it would enter the category of science fiction.

In fact, his first novel, 'Pascual López. Autobiografía de un estudiante de medicina (Pascual López. Autobiography of a Medical Student, 1879)' had a rational resolution for the extraordinary phenomenon, and therefore, it would enter the category of science fiction. Names such as those of Ángeles Vicente or María Lafitte, Countess of Campo Alange, whose unrealistic production is very interesting, are cited, as well as the stories of Roser Cardús, Alicia Araujo, Rosa Fabregat or Teresa Inglés (to mention some of the authors who published in the first part of the 20th century), in addition to Rosa Montero, Sara Mesa, Elia Barceló or Nieves Delgado, among a list of 30 authors.

Another publication related to this line of research has been 'Insólitas. Narradoras de lo fantástico en Latinoamérica y España' (Unusual. Storytellers of fantastic in Latin America and Spain) It is an anthology that I have prepared with the writer, essayist and journalist Ricard Ruiz. In this book we show a global overview of what Latin American storytellers are currently writing in the genre of the unrealistic tale, and we believe readers will be surprised by the large list of authors who are cultivating the fantastic, science fiction and fantasy in the Hispanic environment.

And I cannot fail to mention 'Fantastic Short Stories by Women Authors form Spain and Latin America', whose publication I whose publication I edited together with Patricia García, a colleague from the Department of Spanish Philology, Communication and Documentation and the GILCO Research Group of Universidad de Alcalá, the aim of which bilingual publication was to bring spanish fantastic literature closer to universities in the Anglo-Saxon field.

There is still a lot of work to be done, and we are sure that we will be able to increase the number of Spanish science fiction writers. It´s important to remember that literature theorist and literary critic Harold Bloom, author of 'El canon occidental' ('The Western Canon'), baptized the first demands of feminist and post-colonial literary criticism as the 'School of Resentment', which requested a revision of the literary canon in the curricula of American universities. The canon, like everything else, is configured on the basis of social conventions and class, gender and sexual power relations, which cannot go unnoticed by readers, critics, academics or institutional discourse. If we analyze the presence of the authors in the curricula of secondary education and Spanish universities, we still find that there is much work to be done. On the other hand, my lines of work currently focus on post-humanism and future studies.

Publicado en: Inglés